You can search the internet and find thousands of articles claiming that a series of exercises are the most effective to improve sports performance or mitigate a specific injury. This got me thinking, why are there so many articles and why are so many people searching for them?

I have spent over 20 years working in Strength and Conditioning, 16 of them supporting some of the best athletes in the world (including British and Chinese Rowing). I have yet to specifically focus on a single exercise to improve performance or reduce injury risk. Yet, many articles advocate exactly that. There is clearly a gap between what we perceive we need versus the reality of what we need.

Outcome vs Method in strength training for rowing

“If I had an hour to solve a problem, I’d spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and 5 minutes thinking about the solutions.” Albert Einstein

My experience working with 100’s of athletes using an outcome led approach has resulted in superior results to a methods led approach. It is first worth exploring the difference between an outcome led approach to training and how this differs to the abundance of articles discussing exercises as a methods led approach. Any article that focuses on a series of exercises as a remedy for performance or injury reduction focuses on the methods. The generic implication is that if you include these exercises within your training, you will improve performance or reduce your injury risk. This disregards the intended outcome, the individual, and the task we need to improve. The focus is on improvements within the exercise and not the end goal. This makes a huge leap of faith that by doing exercise ‘x’, it will improve task ‘y’, or being rowing specific, if you back squat, it will make you row faster – this is an overly simplistic view and is frankly not the case.

An outcome led approach invests time to understand the demands of the task first and then understands what changes we as individuals need to make to meet the task demands. The exercise is simply a tool to achieve that demand and is entirely subservient to the outcome. For example, there is good evidence there is a relationship with maximal force expression of the knee and hip with rowers short ergo sprints and 2k performances (Ingham et al 2002, Buckeridge et al 2012). Improving 2k performance is a clear intended outcome. An outcome led approach focuses on this outcome first and then works backwards to determine how we can improve this. In this example, we know that developing the maximal force expression of the knee and hip can contribute to performance. Lastly, we then apply the most appropriate exercise to achieve an improvement in maximal force expression such as using a back squat or leg press.

The exercise is simply a tool to achieve that demand and is entirely subservient to the outcome.

An outcome led approach does not indicate what that exercise is as there are many ways to achieve the same outcome, all of which are context and individual specific. My experiences in rowing suggest that most rowers have a compromised lumbar spine. This means exercises that place load through the spine such as loaded squatting or deadlifting have limited impact on the intended outcome of improving knee and hip maximal force expression. At best, the lumbar spine becomes the limiting factor in that it cannot tolerate the very heavy loads required to meet the intended outcome. At worst, heavy loading exacerbates the lumbar spine which could result in pain or injury. An outcome led approach takes this potential risk into consideration and then allows us to identify an alternative task to complete to achieve the intended outcome. In this example, using the leg press or leg extension may be an appropriate task to increase the maximal force expression of the knee and hip while not compromising the Lumbar spine.

Strength training for rowing is a problem-solving task

“If you define the problem correctly, you almost have the solution.” Steve Jobs

An outcome led approach should be viewed as a problem-solving task. Problem solving has two distinct components. The first is the clarity of outcome and the second is the availability of solutions (the methods we have available to solve the problem). An outcome led approach first focuses on gaining clarity on what the real problem is – it attempts to understand the current state and identify what the future state needs to be. In the example above, the current state is low maximal force expression of the knee and hip. The future state is an increased maximal force expression of the knee and hip. This creates the gap in which applying our solutions try to narrow. When we are clear on this outcome, we can be specific with our solutions to narrow this gap to get closer to the intended outcome.

An outcome led approach first focuses on gaining clarity on what the real problem is – it attempts to understand the current state and identify what the future state needs to be.

I have had many discussions debating the merits of outcome and methods led approaches. However, when we agree to view this as a problem-solving task, it is entirely illogical to apply any available method to an unclear outcome. We must first define the outcome before applying the available methods (the exercises). A simple analogy would be when our engine management light illuminates on our car dashboard. We do not suddenly start filling the car with oil or coolant or replace filters hoping this resolves the unknown problem. We first diagnose the problem which provides the clarity of outcome. Only then do we apply the solution to solve the problem. We are clear what must change and clear how we go about making that change. Training is no different. When we read articles claiming to have the exercises to improve our performance or reduce our risk of injury, it is akin to trying to repair the car without knowing what is wrong with it. We should view our training in the same way.

Returning to the beginning…

“When we change the way we look at things, the things we look at change.” Wayne Dyer

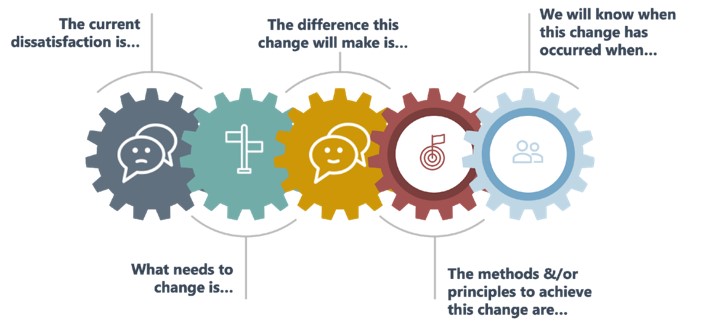

I started the blog by asking the questions of why many articles are claiming to have exercises to improve performance and why are so many people searching for them. The articles exist because we search for them. We search for them to find something we can do to attempt to improve our performance. We jump straight to trying to find a solution before really taking time to understand what our intended outcome is. However, now that we are armed with the idea that we are only trying to problem-solve, we can apply problem-solving principles to identify what we really want to change and why. Figure 1 provides a simple change framework which can help us problem-solve more effectively.

Figure 1: Change Framework

Step 1 is to identify the current dissatisfaction – why is there a need for change? Step 2 focuses on identifying what specifically needs to change. Step 1 and 2 creates the gap between the current and the future state. Step 3 focuses on identifying what any change you decide to make will have on performance or reducing the risk of injury. This is important to include and is often left out. Will it make the boat go faster – what specifically will make it go faster? Step 4 identifies the methods required to achieve the change. This is where the exercises or tasks and how they are applied will be determined. Finally, in step 5, how will you and others know once this change has occurred? We must be accountable to the change and understand what change needs to occur for us all to recognise the intervention to be successful. Without this, we have no way of knowing what has happened.

If we choose to view training from an outcome led approach with a problem-solving mindset, we are far more likely to achieve our desired outcomes. This is more of a mental model and way of thinking and not a method or a training system. It takes more time and when we start to apply this, can feel challenging. However, if we continue to think like this and apply the principles from the framework, the changes we make will be far more reaching than applying exercises from any generic article claiming to have a one size fit all solution. We have the opportunity to truly tackle our training needs thinking about what we really need to affect and explore how we may best do this.

FAQ’s in Rowing Strength Training

How do you increase your rowing strength?

If we define strength as the ability to apply maximal force, we need to put our body parts under greater load than what we can already complete. For example, if our knee can produce 100kg of load during a rowing stroke, to increase our rowing strength, our knee must undergo loads greater than 100kg. This may not be achieved in a boat or on an ergometer. We will most likely need long-term exposure to strength training, using the principles of adaptive overload. Find out more.

Is rowing a strength training exercise?

The simple answer to this is no. Novices are likely to see changes in strength from rowing but as we become more accustomed to rowing, we are very unlikely to see significant changes in our strength or force qualities. When we return to rowing after a period of no rowing such as between the end of one and the start of another season, we again may see small changes in strength. There are significantly more effective methods to develop strength and force qualities than rowing.

How do you get stronger legs for rowing?

The article has focused mainly on an outcome led approach. If the intended outcome is to increase the strengths of the legs, there are multiple methods that can be used. It is less about the exercise and more about the adaptive overload principles to ensure that the legs are exposed to high enough loads to create the correct adaptation for increases in strength and force. The following link provides excellent guidelines on effective strength training.

Why is strength important in rowing?

Rowing is approximately 30% anaerobic in nature demonstrating strength qualities do play a factor in racing (Secher 1975, Secher 1993). The start and the sprint finishes are obvious areas we can observe strength being important. However, increases in stroke rate requires a degree of strength to be able to quickly lift the rate and maintain a higher force output. Rowing economy is also affected by our maximal strength. If we produce 800 Newtons of force on average per stroke, with a maximum of 900 Newtons, we are working at about 89% of maximum capacity. If we increase our maximum to 1000 Newtons, this drops to 80% of maximum capacity. Our economy has improved so we are working less for the same output. Alternatively, we could remain working at 88% of our maximal capacity and produce about 890 Newtons. Finally, smaller boats have lower stroke rates than bigger boats and less people to produce force to move them. Smaller boat rowing may require us to have larger strength requirements than bigger boats.

How often should rowers lift?

The intended outcome will determine how often we should be lifting. However, there is generally more lifting in the winter months than in the spring and summer. In the winter, lifting maybe between 2-4 sessions a week depending on the need and outcome. As we get closer to competitions, this tends to drop to 2-3 sessions. It is important to note however, if there are periods of 10 or more days between lifting, my experience and some unpublished research suggests the start of a decline in strength and force characteristics. So, if trying to maintain a specific strength quality, training should be organised so there is less than 10 days between sessions.

Find out more about how Ludum can help reduce the risk of injury of athletes through the building of strong data-backed training plans.

View more content like this

America's Cup Team Ineos Grinder & Olympic Rower Matt Gotrel interviewed in Crossy's Corner

You could be forgiven for thinking that Matt Gotrel switched from Rowing to Sailing, but he actually switched from Sailing to Rowing (won an Olympic

Jack Hargreaves - Australian Rowing's Double World Champion in Crossy's Corner - Part 1

You could be forgiven for thinking that Matt Gotrel switched from Rowing to Sailing, but he actually switched from Sailing to Rowing (won an Olympic

Jason Osborne - 2020 UCI CyclIng Esports World Champion & Olympic Rower interviewed in Crossy's Corner

You could be forgiven for thinking that Matt Gotrel switched from Rowing to Sailing, but he actually switched from Sailing to Rowing (won an Olympic